On the Four Knights Problem

Thanks to Lovro Šubelj, I recently revisited the four knights problem for the first time in almost a decade.

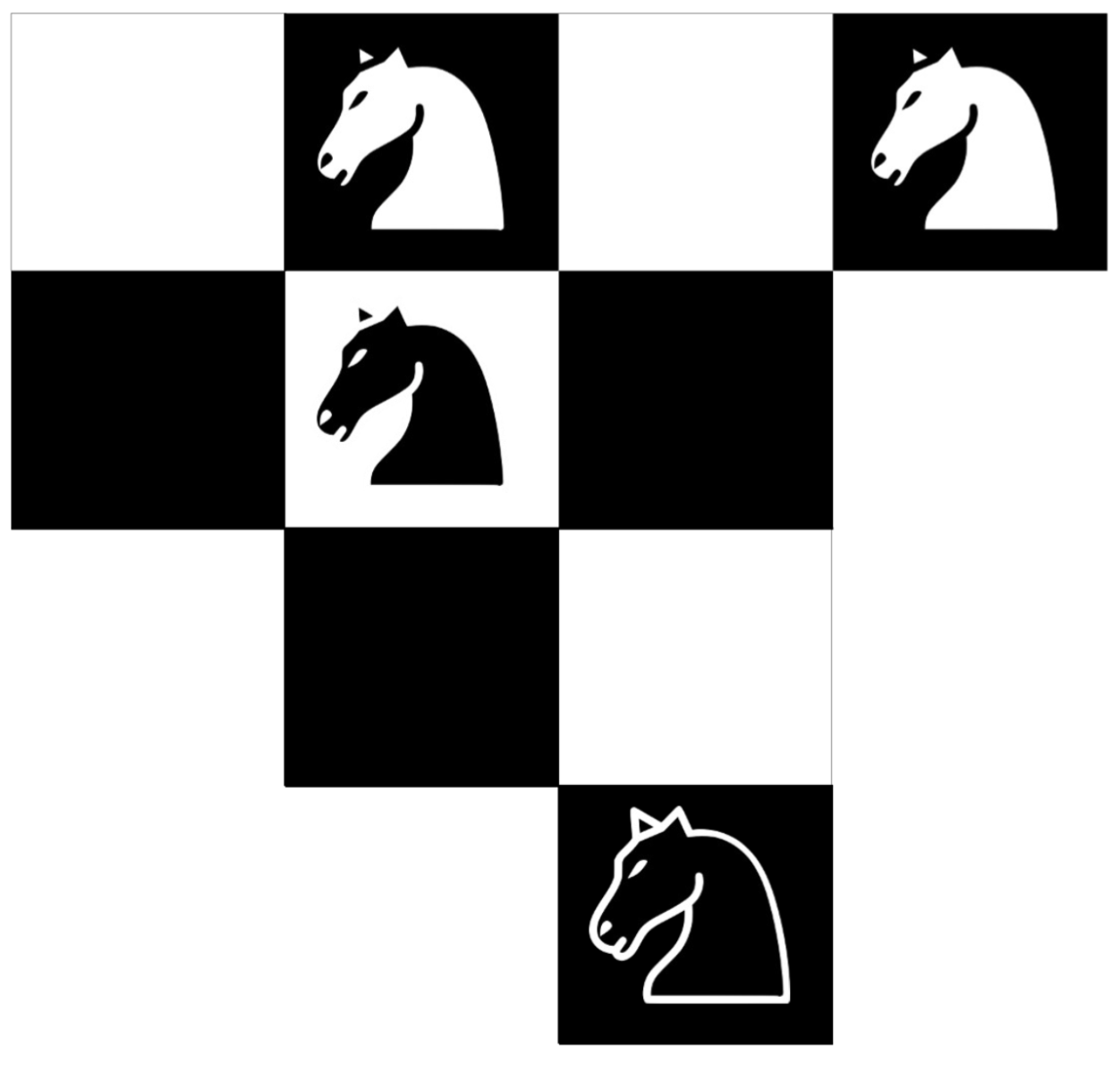

The problem is as follows:

You are given a section of a chessboard consisting of 10 squares. Two white knights and two black knights are placed on it. Your task is to swap the positions of the white and black knights using the fewest possible moves. Try to solve this within one minute.

I was delighted to see this problem reappear as an introductory example in Lovro’s course on machine learning with graphs. It brought back memories, since this problem was one of the the first problems that drew me into graph theory a decade ago, back when I was still in high school. At the same time, I was surprised by how few students in our department knew about it. For me, the problem represents a prime example that demonstrates how graph (or network) representations can make certain problems far easier to approach than representations in Euclidean space. The lack of recognition (in our department) motivated me to write a blog post on the problem, in the hope of introducing more people to it.

The minimal solution of the problem is, to the best of my knowledge, 40 moves shown in Fig.2 as gif:

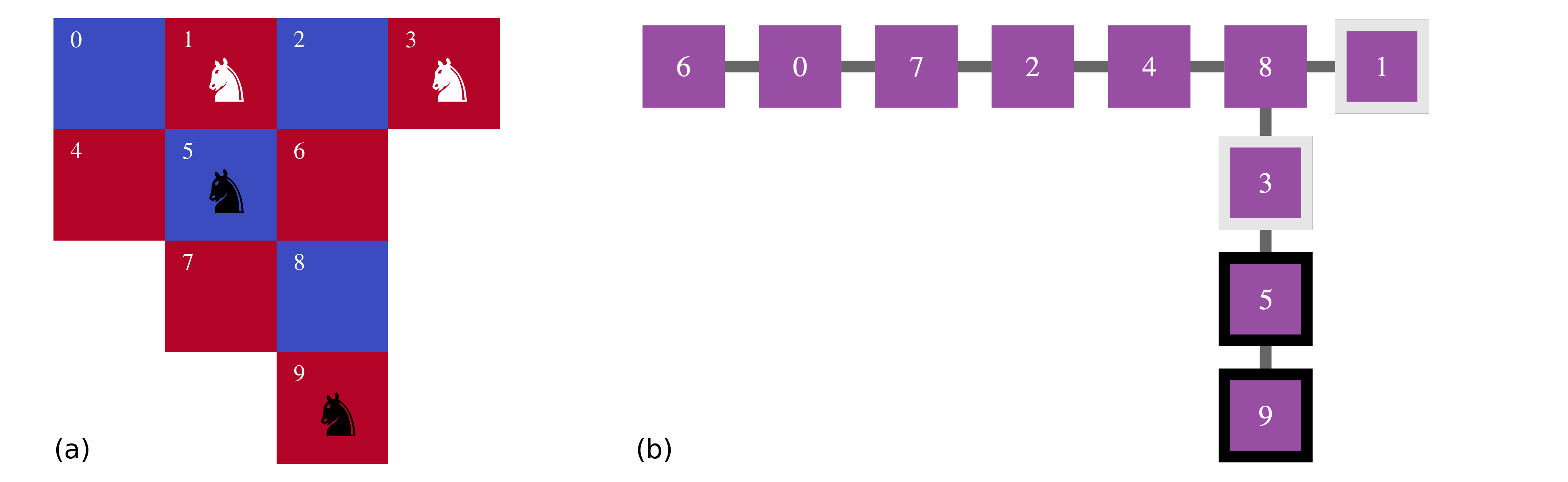

While the animated solution in Fig.2 looks quite intricate on the chessboard, it looks completely different when you represent the chessboard tiles as a graph with knight moves as edges.

To swap the positions of the black and white knights in the graph [Fig.3(b)], the strategy is clear:

- Move the three knights in the vertical branch to the left horizontal branch.

- White knight on vertex 3 \rightarrow vertex 7 (4 steps)

- Black knight on vertex 5 \rightarrow vertex 2 (4 steps)

- Black knight on vertex 9 \rightarrow vertex 4 (4 steps)

- Move the white knight in the right branch (vertex 1) to the vertical branch.

- White knight on vertex 1 \rightarrow vertex 9 (4 steps)

- Move the black knights in the left branch back to the vertical branch.

- Black knight on vertex 4 \rightarrow vertex 5 (3 steps)

- Black knight on vertex 2 \rightarrow vertex 3 (3 steps)

- Move the white knights in the left branch to the right branch.

- White knight on vertex 7 \rightarrow vertex 1 (4 steps)

- Move the black knights in the vertical branch back to the left branch.

- Black knight on vertex 3 \rightarrow vertex 2 (3 steps)

- Black knight on vertex 5 \rightarrow vertex 4 (3 steps)

- Move the white knight in the right branch to the vertical branch.

- White knight on vertex 1 \rightarrow vertex 5 (3 steps)

- Move the black knights in the left branch to the right and vertical branches.

- Black knight on vertex 4 \rightarrow vertex 1 or 3 (2 steps)

- Black knight on vertex 2 \rightarrow vertex 3 or 1 (3 steps)

The total number of steps adds up to 40 steps.

In Fig.4, what appeared to be complicated 40 moves on the chessboard is a series of short walks in a tree.

Why this matters

Many real-world complex systems are spatially irregular: (i) The degrees (or coordination numbers) of their components vary considerably. (ii) Medium- to long-range connections/correlations often play critical roles in shaping their structure and dynamics. The four knights problem possess these two typical aspects of complex systems: not every square has the same degree, and knights moves to third (non-vertical/horizontal) neighbors rather than adjacent ones. Such dynamics are not intuitive in Euclidean space, but once projected onto a graph, their underlying simplicity often emerges.

Back to top